Pakistan and India will mark their 77th years of independence next month. Allama Mashriqi, a visionary leader, foresaw partition as a British strategy and warned of its catastrophic consequences: genocide, atrocities, human rights violations, displacement, chaos, sexual violence, property destruction, and regional instability. Time has proven Mashriqi’s vision accurate, as partition indeed led to widespread atrocities and fueled lasting hatred, disrupting regional peace.

Throughout history, Allama Mashriqi’s pivotal role in opposing India’s partition and ending British rule has been deliberately concealed. Educators and historians, prioritizing career advancement over historical accuracy, have distorted historical facts by promoting state narratives that breed animosity, while hiding Mashriqi’s significant contributions.

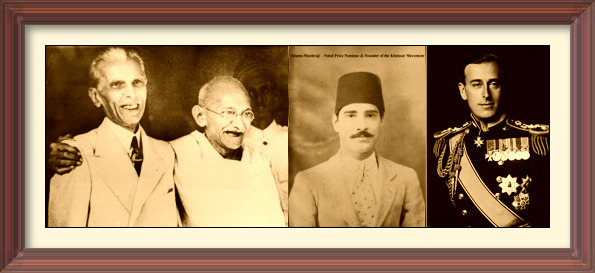

Before delving into the article, it’s essential for the reader to understand that to maintain control over India, the British established civil services, police forces, and armed services, enlisting both Muslims, Hindus, and other non-Muslims. Similarly, they also fostered political leaders who, driven by career aspirations and fame, were willing to collaborate with them. However, these leaders either failed or did not make any effort to mobilize armed revolts. Mohammad Ali Jinnah and Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi are notable examples. In his Urdu book “Hareem-e-Ghaib,” Allama Mashriqi wrote, “O Mashriqi, the nation whose own become strangers, that community is destined to meet death in the end.”

According to Al-Islah dated March 8, 1946, Mashriqi succeeded in instigating the Bombay Naval Mutiny. He was the only frontline leader who supported the mutiny, viewing it as a legitimate uprising against British colonial rule. However, Jinnah, Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, and Vinayak Damodar Savarkar did not stand with the mutineers. The lack of support led to the demise of the uprising, and the mutiny quickly faded. Once again, the British succeeded in maintaining their rule. Shortly thereafter, the Cabinet Mission arrived, but it too failed.

By 1946, all efforts—from the Cripps Mission to the Jinnah-Gandhi talks, the Shimla Conference, the Cabinet Mission, and the London Talks—had failed. The British rulers’ purported efforts were merely a facade, concealing their true intention to retain control without any genuine plans to leave India. Mashriqi, well aware of British strategies, including their manipulation of Muslim and Hindu leaders, became sick of British games. Consequently, Mashriqi planned a coup at the Khaksar Camp in Peshawar in November 1946 and delivered an anti-British speech, which was reported in Al-Islah on December 1, 1946. In response, British Prime Minister Clement Attlee swiftly announced on February 20th, 1947, that power would be transferred no later than 1948. For more details, please refer to my published works.

Mashriqi assessed Attlee’s statement as a ploy to raise national hopes that freedom was coming. To him, behind the scenes, the British were going to fuel the ongoing killings into cataclysmic riots between Muslims and non-Muslims through their trusted leaders. Attlee’s ultimate plan was then to declare that India was unprepared for self-rule, thereby justifying continued British rule. If this scheme failed, another was always ready to be deployed.

Recognizing the deception, Mashriqi ordered 300,000 Khaksars to assemble in Delhi on June 30, 1947, as reported in The New York Times on July 1, 1947. The objective was to seize key vital sites such as the Viceroy’s Lodge, radio stations, and newspapers, and then proclaim the end of British rule. British authorities became alarmed, fearing Mashriqi might take control of India, which would have embarrassed the British Empire globally. Consequently, Lord Mountbatten, the last Viceroy, hastened the power transfer soon after his arrival on March 23rd, just 23 days after Mashriqi’s order, without any justification other than the Khaksar assembly.

Mountbatten held urgent meetings with Muslim and Hindu leaders, discussed his partition plan, and then hurried to London. Upon his arrival in England, he held urgent meetings with General Lord Ismay and Prime Minister Clement Attlee and apprised them of the perceived danger. This created panic, prompting the British Cabinet to approve his plan for a country as vast as India within five days—a challenging task even for a province.

Without delay, Mountbatten promptly returned to India, inviting Jinnah, Gandhi, Nehru, and others to approve his plan. According to Khaksar sources, he warned them that if delayed, the Khaksars’ assembly was scheduled for June 30th, with the government lacking the resources to counter armed Khaksars. By this time, Mashriqi’s Al-Islah journal had published details linking the mutineers to the Khaksar Movement, including the presence of Khaksar flags on Naval ships during the mutiny. Thus, the British were aware of the potential allegiance of the mutineers, so the armed forces would be with Mashriqi rather than the Government.

Identifying the gravity of the situation, Jinnah and Gandhi swiftly accepted partition to prevent Mashriqi from ascending to power. Jinnah shifted from opposing the division of Punjab and Bengal to accepting truncated Pakistan. Gandhi, who had previously advocated for a united India, now favored partition. Following Mountbatten’s directives, Jinnah promptly convened the All-India Muslim League and gained approval on June 9th, while Gandhi appealed to the Indian National Congress and secured approval on June 14th. Both parties agreed to partition within hours of their meetings, all done two weeks before the Khaksar assembly. The speed at which they decided the future of India demonstrates their fear of Mashriqi’s potential rising to power.

Not only that, the panic also led to a quick transfer of power, which is obvious from the following: on Mashriqi’s order of March 1, by June 30th, well over 100,000 Khaksars, despite strict measures by the government to prevent assembly, had reached Delhi, and more were on the way. According to the dailies The Tribune and Dawn both dated July 2, 1947, seventy to eighty thousand Khaksars were in Delhi. As per the National Institute of Historical & Cultural Research’s publication on the Khaksar Movement, “On the 2nd of July, the gathering that took place across the Jumna bridge could not have occurred without the orders of a very powerful authority. On this date, the gathering at the Jama Masjid in Delhi was so immense that, without exaggeration, there was literally no room to place even a sesame seed. And in the grounds, there were more than two hundred thousand people who participated in the Khaksar demonstration.” However, dishonest historians omit this important information, and no educator mentions it to avoid giving credit for ending British rule to Mashriqi.

Since Mashriqi ended British rule, it provoked intense resentment from the British establishment towards him. As a result, credit originally due to Mashriqi was redirected towards Jinnah and Gandhi. Consequently, all promotions such as those in books, academic conferences, films, documentaries, statues, plaques, and road names were denied to Mashriqi and reserved for Jinnah and Gandhi. Jinnah was celebrated as the architect and founder of Pakistan, while Gandhi was hailed as the champion of India’s freedom. Scholarships were established, and educators and students were encouraged to endorse the British Establishment’s narrative by focusing predominantly on Jinnah and Gandhi. Libraries were stocked with materials about Jinnah and Gandhi to facilitate research, while very little was made available about Mashriqi, except for anti-Mashriqi British files, which hindered proper academic exploration of his role.

Museums were barred from displaying his and the Khaksar Movement’s artifacts but displayed Jinnah and Gandhi’s material. The University of Cambridge, where he achieved historic academic milestones, lacks a plaque honoring him as one of its distinguished alumni, and no photos or documents from Mashriqi’s time there have been released.

Furthermore, educators from the Indian subcontinent were hired to promote Jinnah and Gandhi, thereby reinforcing the British establishment’s narrative on the freedom movement and the partition of India. Academic journals and publishers eagerly disseminated narratives that portrayed these figures as central to India’s independence struggle.

It is astonishing that Mountbatten attended Gandhi’s funeral and expressed sorrow. Later, Queen Elizabeth II paid respects at both Jinnah’s grave in Pakistan and Gandhi’s memorial in India during her visits. Additionally, two British Prime Ministers separately visited Gandhi’s memorial. Such honors are rarely extended by those whose rule was supposedly ended by the individuals they honor. Through these honors and the promotional methods mentioned above, the British establishment itself confirmed that Jinnah and Gandhi were tools who facilitated the partitioning of India.

Despite Mashriqi’s funeral being one of the largest in the world, it was not recorded by the British establishment. Neither the Queen, Mountbatten, nor any high-ranking officials sent condolence messages. These suppressive methods serve as evidence that Mashriqi effectively ended their rule.

British enmity towards Mashriqi is understandable. However, the dilemma lies immediately after the creation of Pakistan and India: to discredit Mashriqi and diminish his prominent role, both Jinnah’s and Nehru’s governments cracked down on the Khaksar Movement, confiscating the party’s materials. Moreover, Khaksars in both countries faced severe harassment, including physical assaults, and many were forced to destroy their materials, which they did. One notable Khaksar, Mohammad Ashraf Sandoo from Rawalpindi, ended up burning the documents, as revealed to me by his late son, Lt. General Hamid Javaid.

It is condemnable that academics, instead of looking at the facts, followed their previous British masters and adhered to the state narrative. They started writing books and academic journals promoting Jinnah and Gandhi as heroes and champions, while presenting Mashriqi as insignificant or a villain. Oxford University Press, which holds a major share of the market in many countries, did not publish materials on Mashriqi but actively encouraged publications on Jinnah and Gandhi. The same trend was observed in academic journals. None of these educators ever demanded the declassification of Mashriqi’s documents to write a balanced history. They never demanded that Khaksar Movement artifacts be kept in British, Pakistani, Indian, and Bangladeshi museums or raised a memorial in Lahore similar to the one for the people murdered in Jallianwala Bagh, to recognize the brutal murder of Khaksars on March 19th, 1940.

Unfortunately, many educators either lack political acumen and a deep understanding of world politics, or they are biased. This is evident from their failure to grasp why the British would honor Jinnah and Gandhi while suppressing Mashriqi. Most of them have very poor knowledge of Mashriqi, as they cannot provide political differences between Mashriqi and Jinnah, or Mashriqi and Gandhi, as evidenced by their published works. If they do possess such knowledge, their bias likely prevents its inclusion. It is perplexing that these academics cannot comprehend why the British swiftly approved partition. Equally puzzling is their inability to understand why Jinnah and Gandhi agreed to partition without even knowing the borderlines immediately after Mountbatten returned to India and met with them. These observations highlight their shortcomings in political analysis, understanding of global affairs, and interpretation of historical events.

Historians’ complete reliance on documents is flawed. For instance, if Mountbatten claimed he was anti-partition, it might have been for political reasons or to pressure those opposed to a united India to come to terms with him. Similarly, if Gandhi made an anti-British speech, it could have been to create a false impression of his opposition to the British. Thus, blind reliance on documents is faulty; one must analyze the ground realities as well.

Furthermore, some historians claim that the British left India as a result of riots. They should acknowledge that men and women Khaksars were actively saving the lives of Muslims and non-Muslims alike. According to them, learned from victims, these riots were instigated by the British themselves (and the All-India Muslim League) to create a chaotic environment and justify the continuation of their rule. They fail to understand that Mountbatten had no urgency to leave India; he stayed there even after the partition. Their claim that Jinnah single-handedly created Pakistan and is solely responsible for founding the country is an oversimplification of the facts. They appeared unaware that Pakistan was a British creation for their vested interests, intended to foster hostility in the region to facilitate arms and technology sales. Jinnah was merely used to establish the country; otherwise, he had no grassroots power to even prevent the partition of Punjab and Bengal. Moreover, some have put forward dubious claims, such as the assertion that the British departed India due to economic weakness after World War II. It’s important to understand that India was regarded as the prized possession of the British Raj, with its abundant resources poised to aid in rapid recovery from wartime losses. These assertions overlook historical realities. Additionally, there is a failure to recognize that fabricating historical narratives is not an act of patriotism; rather, it is dishonest and a deliberate effort to undermine genuine understanding and respect for historical truths.

Another troubling aspect is that by emphasizing Jinnah and Gandhi’s confrontational politics, these educators, knowingly or unknowingly, perpetuate hatred between Muslims and Hindus and strain relations between India and Pakistan. This approach also fuels fundamentalism and provokes animosity. Moreover, it is bewildering that these academics and the global community, including human rights activists, largely overlook the consequences of partition. It resulted in massive killings, displacement of millions, and other atrocities. It also led to ongoing hostility between Pakistan and India. If leaders in Europe had caused such devastation through politics, they would have been deemed criminals and charged with crimes against humanity—Adolf Hitler being a prime example. However, this standard has never been applied to Jinnah and Gandhi.

The history is heavily biased and manipulated, focusing primarily on leaders acknowledged by the British establishment. In reality, figures like Mashriqi, who refused to collaborate with the British, played significantly more impactful roles. The Khaksar Movement, for example, mobilized masses against British rule on a scale that far surpassed the influence and combined impact of Jinnah and Gandhi. To claim that Jinnah and Gandhi’s politics led to the British quitting India is naive and childish. In the Indian subcontinent, reclaiming land unlawfully seized by deceitful individuals is nearly impossible, let alone attributing the British departure from India to the ineffective methods of Jinnah and Gandhi.

To uncover the truth, I have extensively published and produced a documentary titled “The Road to Freedom: Allama Mashriqi’s Historic Journey from Amritsar to Lahore.” This 2.5-hour documentary presents compelling evidence that the British expedited their departure due to the power of Mashriqi. For a quick understanding of the facts, watch short clips numbered from 40 to 53 from the documentary. Additionally, I have authored a newspaper article titled “The British Chessboard: Jinnah, Gandhi, and the Strategic Divide of India,” further exploring these dynamics and their impact on India’s partition and subsequent history.

Social media has enabled the wider dissemination of diverse perspectives on historical events. I am pleased that my views on Allama Mashriqi’s pivotal role, critiques of Jinnah, Gandhi, the Two-Nation Theory, and the partition of India are gaining attention. My criticism over the last 28 years, since I began my research, was not meant to demean anyone but rather to reveal the reality and eliminate, or at least diminish, the hate that fabricated history has created between Muslims and Hindus. It has finally brought the desired results. Recently, academics and intellectuals in Pakistan are openly criticizing Jinnah, the Two-Nation Theory, and questioning the rationale behind Pakistan’s creation. In India, I have heard that half of the population no longer views Gandhi as the sole champion of India’s independence, with critical comments on both Jinnah’s and Gandhi’s political legacies becoming more prevalent.

Global propaganda, systematic indoctrination, and deliberate misinformation that once portrayed Jinnah and Gandhi as heroes, while marginalizing Mashriqi, are rapidly changing. This trend is expected to continue as more people critically engage with historical narratives. Falsehoods have a limited lifespan; truth inevitably emerges.

Scholar and Historian Nasim Yousaf has, to date, dedicated 28 years to documenting the history of the Indian subcontinent, starting in 1996. As the grandson of Allama Mashriqi, he has authored 19 books and digitized 19 rare works. His latest book, “The Khaksar Women: Warriors for Independence,” is available in hardcover and Kindle formats. Videos detailing Mr. Yousaf’s biography and books, carried by libraries worldwide, can be found online.

Copyright © 2024 @NasimYousaf