By Nasim Yousaf

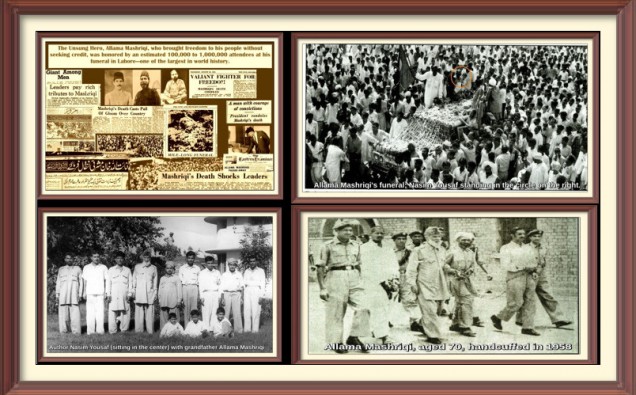

Allama Inayatullah Khan Al-Mashriqi (1888-1963), a valiant freedom fighter and founder of the Khaksar Movement, passed away on August 27, 1963. His funeral, which I witnessed at around the age of 10 on August 29, 1963, in Lahore, was one of the largest in world history, with estimates of the crowd ranging between one hundred thousand and one million mourners. This article commemorates the 61st death anniversary of Mashriqi and offers a detailed account of the funeral attended by his devoted followers and admirers.

Mashriqi’s political life was marked by constant struggle. In 1958, at the age of 70, he was imprisoned under false murder charges related to the killing of former Chief Minister of West Pakistan, Dr. Khan Sahib, during President Iskandar Ali Mirza’s government. Despite Lieutenant Colonel Ilahi Bakhsh—who had been Mohammad Ali Jinnah’s doctor during his final days—informing the court of Mashriqi’s serious illness, Mashriqi was still brought to court handcuffed, mistreated, and mishandled during his confinement. Due to poor food, mental and physical torture, and inadequate medical treatment, his health continued to deteriorate. Ultimately, no evidence was proven against him, and on November 17, 1958, Mashriqi was honorably acquitted of the murder charge. Upon his release, Mashriqi stated:

“The undesirable torture I have been put to by the previous Government for uncommitted crimes will remain a landmark in the history of corruption and tyranny for all time…My suffering almost to the point of death that I had to face at the hands of the political tyrants, has not gone in vain and I am happy that truth and righteousness have at last won a battle like of which has, perhaps seldom happened in the history of the defeat of evil.”

Despite the challenges he faced, including a deadly disease, he remained resilient. Yet, his once-strong body grew weak and accustomed to pain. I vividly remember my visits to his house—how I would press my beloved grandfather’s legs and feet, hoping to bring him some relief from the aches that burdened him. Those moments were my small way of comforting him.

The intention behind implicating Mashriqi in a murder case was to execute a judicial murder disguised as a legal process, aiming to secure his execution through a court verdict. However, the evidence against him was exceedingly weak. The police’s main witness, Khursheed Khalid, a prominent Khaksar, had been beaten and coerced into testifying against Mashriqi. When Khalid later recanted his statement, admitting that it was false and made under duress, the entire case collapsed like a house of cards. I have covered this fictitious case in detail in my 450-page book titled “Allama Mashriqi Narrowly Escapes the Gallows: Court Proceedings of an Unpardonable Crime Against the Man Who Led the Freedom of the Indian Subcontinent.”

Though Mashriqi was freed, as time progressed, his health continued to deteriorate. On August 8, 1963, he was admitted to Albert Victor Hospital, which was part of Mayo Hospital in Lahore. News of Mashriqi’s condition was reported daily in newspapers across the country. Dignitaries, along with a large number of Khaksar followers and admirers, began visiting the hospital to see their ailing leader. Many offered blood donations and volunteered to nurse him. Letters and phone calls inquiring about his health poured in from across the country and abroad, ringing in the hospital, Mashriqi’s home, and among his relatives and followers. Special prayers were held both within Pakistan and abroad for his early recovery.

On August 12, President Mohammad Ayub Khan called the hospital to inquire about Mashriqi’s health and offered him medical treatment in Switzerland at the government’s expense. However, Mashriqi politely declined the offer, as it was against his principles to use public funds for personal treatment. Additionally, he remarked, “I do not want to die in a foreign land.” On August 24, the President, accompanied by the Governor of West Pakistan, Amir Mohammad Khan, visited the hospital. Mashriqi thanked them for their concern, saying, ‘Aap ka bohat shukriya’ (Thank you very much). Ayub replied, ‘Khuda khair karay’ (May God make you well).

His time came, and Mashriqi passed away on the night of August 27 at six minutes past nine, at the age of 75. The Pakistan Times dated August 28, 1963 reported “A large number of Khaksars, who had . . . been in the surrounding lawns of the hospital since the Allama was admitted and had prayed for the recovery of their leader were shocked into silence. But the first shock at once wore out and the hospital suddenly echoed with sounds of weeping, wailing men and women, the late leader’s relatives and his devoted followers.”

Upon announcing his death, newspapers immediately published special supplements that were distributed across Pakistan. The news was also broadcast on Radio Pakistan, All India Radio, BBC, and other news channels around the world. The news of Mashriqi’s passing spread like wildfire. The next day’s reports made headlines in major newspapers across the country, with articles and editorials describing him and his movement.

The Khaksars arranged a ceremonial burial for Mashriqi. On the night of August 27, at approximately 10:00 p.m., his body was wrapped in the red Khaksar flag, placed on a stretcher trolley, and taken to the mortuary, which was about 300 yards from his hospital room. The trolley, with two Khaksar flags mounted on the sides, was pushed by prominent Khaksars, while others marched in front of and behind the trolley, calling out “Chap Rast, Chap Rast,” the marching command used for synchronizing Khaksars’ steps like military soldiers. The followers of the late leader remained silent as they escorted him to the mortuary, but the monotony of the marching commands was interspersed with suppressed sobs. The sound of their shoes on the metaled road of the hospital broke through the stillness of the night. Inside the mortuary, only a few selected Khaksars accompanied the body. Khaksar guards were stationed at the doors of the mortuary and at various points around the building, where they were to remain for twenty-four hours until the body was taken to its final resting place.

At the hospital, the Khaksars raised the red Khaksar banner, adorned with the white star and crescent moon, in honor of their late leader. They chanted passionate slogans, proclaiming that while the leader was dead, the movement remained alive and would endure forever. In accordance with Mashriqi’s wishes, he was to be buried at the headquarters of the Khaksar Tehreek, adjacent to his house in Ichhra, Lahore, where he had launched his Movement 33 years earlier.

Trains, planes, buses, trucks, wagons, cars, and taxis, all packed with Khaksars and mourners, arrived in the city to attend his funeral. Khaksar camps were set up, including one at the Mochi Gate, where Khaksars from all over the country stayed.

On the day of the funeral, Mashriqi’s wooden coffin was covered with flowers and floral wreaths and placed on an open-roofed vehicle with two Khaksar flags on the sides. The funeral procession began from Mayo Hospital at 8:00 a.m. on August 29, 1963, for its ten-mile journey to Ichhra.

A group of uniformed Khaksars marched in front of and behind the vehicle. Starting from Mayo Hospital, the procession passed through areas such as Bunse Bazaar, Shah Alam Market, Rung Mahal, Chowk Naugaza, and reached the Badshahi Mosque. All business centers, including Shah Alam Market, Azam Cloth Market, Akbari Mandi, Kashmiri Bazaar, Dabbi Bazaar, Alamgir Market, Shoe Market, Furniture Market, Bunse Bazaar, and others, remained closed as a mark of respect for the late leader and to mourn his death.

Around 9:45 a.m., the procession reached Badshahi Mosque for the funeral prayers. The mosque and its courtyard were completely filled, so the masses gathered outside wherever they could find space to join the prayers. The funeral prayers were led by Maulana Abdus Sattar Khan Niazi at 10:00 a.m. Thereafter, the procession began again, heading for its final destination. From the mosque to Ichhra, the procession route included Chowk Naugaza, Tehsil Bazaar, Bazaar Hakiman, Bhatti Gate, Circular Road, New and Old Anarkali, Lytton Road, Mozang crossing, Ferozepur Road, and then to Ichhra. Along the way, people chanted slogans such as Allama Mashriqi Zindabad, Khaksar-i-Azam Zindabad, and Mujahid-i-Azam Zindabad. Zindabad means Long Live.

The funeral procession, overflowing with mourners as far as the eye could see, moved very slowly. While I was standing on the funeral vehicle, I was pushed off into the crowd. Fortunately, some Khaksars immediately picked me up and placed me back onto the vehicle. Had they not rescued me, I would have been crushed under the ocean of faces; there was no room to carve out a space of one’s own.

It was attended by people from all walks of life, including political and religious leaders, members of the National and Provincial Assemblies, cabinet ministers, the Parliamentary Secretary, and other dignitaries. People lined both sides of the roads for the entire route of the procession, and though traffic was rerouted, there were still traffic jams everywhere. Men, women, and children of all ages were on the sidewalks, rooftops, balconies, trees, poles, and anywhere they could find a place to stand. I also saw men and women, children of all ages, crying, sobbing, and beating their chests out of emotion and love for Mashriqi; some of them even fainted. Braving the sweltering heat, the procession participants continued marching, and people stood for long periods to pay homage and take their last glimpse of the departed leader. Throughout the funeral route, people had made arrangements for cool water for those in the procession. Among the crowd were also families whose sons, brothers, and husbands had either been killed during the freedom movement or had suffered the brutalities of prison during the Khaksar struggle for freedom.

There were a number of very intense moments throughout the procession. As the procession reached Chowk Naugaza, the site of the Khaksars’ massacre, guns were fired, and the martyrs of March 19, 1940, were saluted. Khaksars who had lent support to those involved in the massacre were present among the mourners. Another powerful and emotional moment occurred when the funeral reached near the Borstal Jail on Ferozepur Road, the prison where Allama Mashriqi had once been confined. People chanted slogans similar to those mentioned earlier as a tribute to Mashriqi.

All along the route, people were reciting verses from the Holy Quran and showering him with petals in an effort to bid farewell to the departing leader. The abundance of flowers on Mashriqi’s body was so overwhelming that his face could hardly be seen, and the entire route was covered with a carpet of blooms.

The procession eventually reached Ichhra. At that time, out of their love for Mashriqi, the mourners and Khaksars continually kissed me on the head and hugged me, seeking consolation and solace for their grief through their embrace. The Khaksar Tehreek’s flag at the headquarters was flown at half-mast. Before the burial, Khaksars honored Mashriqi with a 101-gun salute, and he was laid to rest with full honors.

The solemn scene at the time of the burial reached its peak when all the men, women, and children began to cry hysterically and sob as Mashriqi was laid into his grave at 2:05 p.m. Mashriqi’s death “ended the illustrious career of a person who fought valiantly throughout his life against the British…by organizing the Khaksar Movement,” wrote the Civil & Military Gazette on August 30, 1963.

The nation seemed to be in a state of shock. The Urdu and English newspapers covered the funeral with these words: “The remains were laid to rest with streaming tears and shaking hands…a shower of flowers at the funeral,” “Mashriqi’s Death Casts Pall of Gloom Over the Country,” and “Mashriqi’s Death Shocks Leaders.” Another called Mashriqi a “Giant Among Men,” and “Lahore’s atmosphere once again echoed with the sounds of Chap Rast.” The papers carried condolence messages from the President, former Governor General, and a large number of other prominent people. Articles and editorials were also written describing him and his Movement.

It is important to remember that at the time of his death, not only was Mashriqi’s role in ending the British Raj still fresh in the public’s memory, but also the attempts to crush him both in British India and later in Pakistan. Mashriqi was arrested about six times in British India and at least nine times in Pakistan. While he faced fewer arrests and less overall confinement under British rule, he endured more frequent arrests and imprisonment in Pakistan, despite his old age. In May 1962, despite suffering from cancer, he was imprisoned in District Jail Rawalpindi, located opposite the Rawalpindi District Courts, which I visited with my parents. This vindictive behavior, which began right after Pakistan’s creation, continued in the country. These experiences, among the reasons, garnered him significant sympathy and admiration, leading to large crowds at his funeral to pay their respects.

According to two newspapers, the funeral procession was one mile long, with 100,000 people in attendance. However, the Khaksar circle reported that the entire 10-mile route was jammed with mourners, estimating the crowd to be up to one million. The Khaksars believed that the state-controlled media often presented distorted facts and figures, which is entirely correct. I recall seeing someone in the crowd, possibly a journalist, trying to film the funeral and being aggressively stopped by the police. This is why no video recordings of Allama Mashriqi versus his contemporaries have ever surfaced. The British establishment, which had significant influence in Pakistan and held a grudge against Mashriqi for forcing their exit from India, sought to suppress his promotion. This suppression of filming was part of efforts to prevent the true scale of the event from becoming widely known. Given the scale of the funeral and the intense emotions involved, I can confidently say that I have yet to witness such a large funeral, which supports the Khaksars’ account of the crowd size. For more details about the anti-British stance against Mashriqi and the fabrication of facts by historians and professors, refer to my published works, including my latest article from July 2024, titled “Allama Mashriqi’s Order: 300,000 Khaksar Soldiers Reach Delhi and the Sudden Collapse of British Rule.”

His death was mourned for a long time, with people constantly sending messages and making phone calls not only to Mashriqi’s house but also to our home, his relatives, and the Khaksars. They would praise him and regard him above any of his contemporary leaders, recounting stories of his bravery, including how Mashriqi ended British rule—details that I have also included in my published works.

Great and remarkable was a man whose life guided humanity, embodying the principles he preached with a saintly purity. Though he is gone, his writings and speeches continue to inspire and direct us. His admirers still mourn his death, feeling a profound sense of loss. In 2023, his funeral was featured in the documentary I produced, titled “The Road to Freedom: Allama Mashriqi’s Historic Journey from Amritsar to Lahore.” Also visit the Facebook page “Nation Mourns Death of Legendary Freedom Fighter, Allama Mashriqi”.

Scholar Nasim Yousaf, a biographer of Allama Mashriqi and other legends in his family, has dedicated 28 years to documenting the history of the Indian subcontinent, beginning his research in 1996. He has authored 19 books and digitized 19 rare works. In addition to his 2.5-hour documentary on Allama Mashriqi, his monumental contributions include digitizing Mashriqi’s historic and rare journal Al-Islah and writing a book on Khaksar women. Detailed information about the scholar’s biography and the world-renowned libraries that carry his books can be found online.