Has a powerful ruler ever transferred power without facing a significant threat to their rule? The Indian sub-continent’s freedom was inconceivable without Allama Mashriqi’s private army of over five million uniformed Khaksars who threatened British rule. Considering this reality, India and Pakistan owe their independence to Allama Inayatullah Khan Al-Mashriqi – a legend and a great freedom fighter.

Allama Mashriqi’s struggle to revive the glory of the Indian nation started with his poetic work, Kharita, which he wrote in his youth (1902-1909). In 1912, Mashriqi discussed his future aims to liberate the nation when he spoke at a graduation dinner (hosted by the Indian Society of Cambridge University in his honor):

“[translation]…Our educational achievements bear testimony to the fact that India can produce unparalleled brains that can defeat the British minds. India is capable of producing superior brains that can make the nation’s future brighter. After we return from here, we must ponder how to break the chains of slavery from the British…We should keep our vision high and enlarge our aims and goals so we can be free from the chains of slavery as soon as possible” (Al-Mashriqi by Dr. Mohammad Azmatullah Bhatti).

Later, Mashriqi’s work Tazkirah (published in 1925) spoke of jihad as well as the rise and fall of nations and was a step towards bringing revolt against British rule. In 1926, Mashriqi embarked on a trip to Egypt and Europe; there, he delivered a lecture on his book Tazkirah, jihad and fighting colonial rule. In Germany, Mashriqi was received by Helene von Nostitz-Wallwitz, the niece of German President Hindenburg (Al-Islah, May 31, 1935). While in Germany, Mashriqi discussed the aforementioned topics with Albert Einstein, Helene, and other prominent individuals; these conversations reflected his mindset of bringing an uprising in foreign lands (as well as in India) against the oppression of British colonial rule. Earlier, while in Egypt at the International Caliphate Conference, Mashriqi succeeded in defeating a British plan to have a Caliph of their choice elected to control the Muslim world. During the trip, Mashriqi acted courageously and ignored the risks of being persecuted or even hanged for treachery against the British Empire in foreign lands…and that too as a government employee.

Meanwhile in India, M.A. Jinnah, M.K. Gandhi, the All-India Muslim League, and Indian National Congress had not taken any concrete steps to bring revolt or overturn British rule. Anyone who attempted to rise against British rule was either ruthlessly crushed or faced the end of his/her political career. As such, Muslim and Hindu leadership adopted ineffective methods such as passing resolutions, taking out rallies and raising anti-British slogans. Mashriqi felt that such methods were useless and would not end the British Raj.

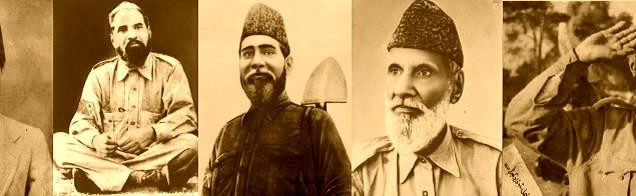

In 1930, Mashriqi resigned from his lucrative job to bring independence to the nation. Risking the lives of himself and his family, Mashriqi launched a private army called the Khaksar Movement. Enrollment in the combative and revolutionary Movement was tough; the masses were not only dispirited, but scared to risk their lives for freedom. In order to promote his mission, Mashriqi traveled in buses, tongas, or third-class compartments of trains and walked for miles at a time in poverty-stricken and rural areas. He was indistinguishable from the common people. This was a man who could have easily accepted an Ambassadorship and title of “Sir” (both of which he was offered by the British in 1920) and continued to draw a hefty salary, brushing shoulders with the British rulers and leading a life of utmost luxury. However, he chose to fight for the people instead.

In 1934, Mashriqi launched the Al-Islah weekly newspaper. The Times of India (August 08, 1938) wrote, “The publication of Al-Islah gave a fresh impetus to the [Khaksar] movement which spread to other regions such as Afghanistan, Iraq and Iran [as well as Bahrain, Burma, Ceylon, Egypt, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Yemen, and U.K].” By the late 1930s, from Peshawar to Rangoon, the private army of Khaksars had grown to millions.

Throughout these years, the Khaksars continued their activities, including military camps where mock wars were held using belchas (spades), swords, batons, and sometime even cannons. Many Khaksars had willingly signed pledges in blood indicating that they would lay their lives and property if necessary for the cause of freedom. The Khaksars paraded in the streets of India and spread their message against British rule, including running slides in cinemas, chalking walls, distributing pamphlets and flyers and through Al-Islah. By 1939, Mashriqi had prepared a plan to oust British rule. Later that year, he paralyzed the Government of U.P. Thereafter, Mashriqi formed a parallel government, published a plan (in Al-Islah newspaper) to divide India into 14 provinces, issued currency notes, and ordered the enrollment of an additional 2.5 million Muslim and non-Muslim Khaksars.

By now, the strength of the Khaksars had been revealed and the British foresaw Mashriqi taking over. Under intense pressure, the rulers began to make promises of freedom for India and started conversations with M.A. Jinnah, M.K. Gandhi, and others. The Government also took immediate action by launching an anti-Mashriqi campaign in the media; Khaksar activities and the Al-Islah journal were banned. A large number of Khaksars were mercilessly killed by police on March 19, 1940. Mashriqi, his sons, and thousands of Khaksars were arrested. Mashriqi’s young daughters received death threats and threats of abduction. Intelligence agencies were alerted. While in jail, life was made miserable for Mashriqi and the Khaksars; many individuals were kept in solitary confinement and several got life imprisonment. While their activities were banned, the Khaksar Tehrik continued operating from the underground; Al-Islah’s publishing operations were moved to other cities (Aligarh and Calcutta). To overcome censoring of mail and phone calls, they employed the use of secret codes. The Government repression brought additional uprise in the country against British rule.

While in jail, Mashriqi was informed that in order to obtain his release, he must announce the disbandment of the Movement; he refused and instead kept a fast unto death that made the rulers fearful of additional backlash from the public and forced them to release Mashriqi after two years in jail without a trial (strict restrictions on his movements remained after release). Thus, Mashriqi, his family, and the Khaksars refused to surrender and the rulers failed to suppress the Khaksar Tehrik.

Upon his release (despite restrictions on his movements), Mashriqi asked Jinnah, Gandhi, and other leaders to form a joint front and stand with him so he could end British rule. He also pushed for a Jinnah-Gandhi meeting and continued to promote Hindu-Muslim unity. However, vested interests prevented these leaders from joining hands with Mashriqi.

As the British continued holding talks with their favored leaders, Mashriqi continuing pushing rigorously for a revolt. In 1946, Mashriqi succeeded in bringing about a Bombay Naval Mutiny on February 18, 1946 (Al-Islah, March 08, 1946), which also prompted mutiny within the other armed forces.

On June 08, 1946, at the Khaksar Headquarters in Icchra (Lahore), Mashriqi addressed a gathering of Khaksars, soldiers released from the armed forces after World War II, and the soldiers of the defeated Indian National Army (INA) of Subhas Chandra Bose: “after sixteen years of unprecedented self-sacrifices, we are now ardent to reach our objective as fast as possible, and within the next few months will do anything and everything to achieve our goal” (Al-Islah June 14, 1946).

Final preparations for a revolt for independence took place in November 1946 at a historic Khaksar Camp in Peshawar (from November 07-10, 1946), where mock wars and military exercises were held. Mashriqi addressed a crowd of 110,000 Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, Christians, and others; he shed light on the self-seeking and futile politics of Indian leaders and gave an account of the British exploitations of India’s resources. The speech sparked a sense that further abuse by the rulers would no longer be tolerated and their rule must come to an end. Thereafter, on December 01, 1946, Mashriqi distributed a pamphlet in India proclaiming:

“[translation] Idara-i-Aliya [Khaksar Headquarters] shall soon issue an order that in the entire India, four million [sources quote a range from 4-5 million members] Khaksars, side by side with hundreds of thousands rather millions of supporters shall march simultaneously…This moment shall dawn upon us very soon and that is why it is being ordered that a grand preparation for this historical day should commence immediately…so that British can clearly witness the day of India’s freedom…”

With this bold announcement, a British hold on power was no longer possible. As such, Prime Minister Clement Attlee announced a transfer of power by no later than June 1948. Mashriqi suspected that the announcement could be a ploy to divert public attention or to buy time to create dissent within the country (for example, by encouraging ongoing Muslim-Hindu riots), so that the British could justify and extend their rule.

To close the door on any such ploys, Mashriqi ordered 300,000 Khaksars to assemble on June 30th, 1947 in Delhi; this order put the final nail in the coffin for the British Raj. Such a huge assembly of this private army of Khaksars would enable them to take over all important installations – including radio/broadcasting stations, newspaper offices, British officials’ lodges, and government offices. Immediately following these steps, an overturn of British rule was to be announced via media. The timing of this coup d’état was fitting, as the entire nation (including the armed forces, who had already revolted against the regime) wanted an end to British rule. With this impending massive assembly of Khaksars in Delhi, the rulers saw the writing on the wall; they feared their humiliation and defeat at the hands of the Khaksars and angry masses. Moreover, the rulers could not accept a united India…and that too at the hands of Allama Mashriqi.

Therefore, without any other compelling reason, a transfer of power was undertaken by the British in an extraordinary rush; on June 3rd, 1947, the Viceroy of India, Lord Mountbatten, announced a plan to partition India. Mountbatten called a hurried meeting of their selected Muslim and Hindu leaders and asked them to accept the plan immediately. The selected leaders saw power falling in the hands of Mashriqi and he becoming the champion of freedom if they did not accept the plan. Jealousy and vested interests came into play. M. K. Gandhi, Jinnah’s All-India Muslim League, and the Indian National Congress accepted the plan almost immediately. Mashriqi tried to prevent the All-India Muslim League from signing off on the plan, but was “stabbed” (The Canberra Times, Australia, June 11, 1947) on the same day that the League accepted the plan (June 09, 1947). It was obvious that the motive of this stabbing was to keep Mashriqi from stopping the partition of India (in order to have a united independence).

The partition plan was accepted and announced all over the world only about two weeks before the assembly of the Khaksars was to take place. Logically speaking, can it actually be called a “transfer of power”? The British handed over control of the nation in a rush because the Khaksars were on the verge of forcibly ending their rule; indeed, over 100,000 (Dawn July 02, 1947 reported “70,000 to 80,000”) Khaksars had already entered Delhi despite strict measures in place.

The establishments in India and Pakistan and historians overstate the role of the British’s preferred leaders, while failing to recognize the reality of what led to independence. Neither Jinnah nor Gandhi had the street power to overturn-British rule; it is for this reason that they were seeking a transfer of power, which they obtained based on the threat posed to British rule by the powerful Khaksar Movement. Historians have thus far presented history from a colonial or Pakistani/Indian state point of view, rather than based on the facts on the ground.

Instead of giving credit to Mashriqi, some historians provide flimsy reasons for the end of British rule. Some of the reasons they cite are:

(1) Gandhi’s methods and Jinnah’s constitutional fight brought freedom to India and Pakistan respectively — this argument is neither supported by human history nor the realities on the ground, as colonial rulers do not voluntarily relinquish their power without a significant threat to their rule.

(2) The British fast-forwarded transfer of power and left quickly to avoid blame for the massive killings that would ensue — this argument also does not make sense as the massive communal riots/killings began on Direct Action Day (August 16, 1946), so an early transfer of power would not have helped the rulers avoid blame. Even if we were to accept these writers’ claims, why would Lord Mountbatten then become the first Governor General of India and why would many Britishers continue to hold important positions in Pakistan and India?

(3) The British left India because after World War II, they became economically weak and could not keep their hold on India — this claim does not hold water. India’s rich resources would have helped them to recover their losses from the war.

(4) The end of the British Raj came about because of Subhas Chandra Bose’s Indian National Army (INA) — the INA was defeated in 1945 and thereafter, Subhas Chandra Bose was not on the scene anymore (he was either killed or went into hiding as claimed).

The Pakistani, Indian, and United Kingdom establishments do not let the truth come out. Despite my open letters to the Chief Justices of the Supreme Courts and the Prime Ministers of Pakistan and India, both countries (and the U.K.) have not declassified Mashriqi and the Khaksar Tehrik’s confiscated papers from the pre-post partition era. In order to hide the truth, Mashriqi’s role is also excluded from the educational curriculum and academic discussions everywhere. The Partition Museum in Amritsar, Lahore Museum, London Museum and others do not display Mashriqi and the Khaksar Tehrik’s artifacts.

Despite the current state of affairs, the ground realities speak loudly to Mashriqi’s heroic fight; without Mashriqi’s private army of Khaksars, the British rulers would not have even come to the table to discuss the freedom of the Indian sub-continent (now Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan), leave alone quit the lucrative sub-continent. As such, both countries owe their independence to Mashriqi and he is a founding father of India and Pakistan.

Nasim Yousaf is a biographer and grandson of Allama Mashriqi. Yousaf’s works have been published in peer-reviewed encyclopedias and academic journals (including at Harvard University and by Springer of Europe), and he has presented papers at academic conferences, including at Cornell University.

Copyright © 2020 Nasim Yousaf